There is deep American history imbued within every stalk of wheat and worn wooden plank in eastern Washington’s Palouse region. I sensed it when I slowed down and quieted my anticipation. I paused intentionally and inhaled the sweet air to further inform my senses. I love the panoramic landscape, big open skies, owls and authentic friendliness of the citizens, but I am even more captivated by their stories and traditions.

.

The region is a must-visit destination for hundreds of photographers each year, and most of them prize photographing their own postcards of the region’s lush rolling fields, looming classic barns and aged industrial vehicles. From what I’ve seen online these past five years, few visitors have taken the time to make photographs that attempt to tell a story about this region. That was my goal last Spring, and will be again when I run my annual Palouse photography workshop there in June.

This pastoral beauty was captured with the XF 16mm f1.4, my landscape and travel favorite. Not too wide, just right.

The Palouse region in Eastern Washington and Idaho holds a bit of mystery in the origin of its name. One theory is that the name of the Palus tribe (spelled in early accounts variously as Palus, Palloatpallah, Pelusha, etc.) was converted by French-Canadian fur traders to the more familiar French word pelouse, meaning “land with short and thick grass” or “lawn.” Over time, the spelling changed to Palouse.

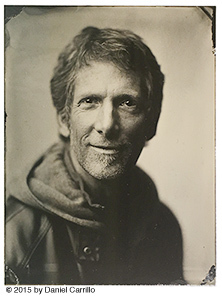

John Aeschliman is a fifth generation farmer, well respected for the progressive ‘No Till’ direct seeding method he uses to greatly reduce erosion and maximize yields from his sloping acreage. This shot used the 23 f2.

The Palouse has long been one of the world’s largest producer of grains and legumes, eternally shifting by necessity to bring other popular food sources to market. In fact, it’s products help feed several countries. Many individuals I’ve met take enormous pride that their families descended from it’s original settlers. It is those generations who have given the region and it’s weathered structures a wonderful personal history told verbally, and also kinesthetically through the heirlooms and implements that remain. I like to focus on the grand vistas but even more so on the beautiful details that hold many of the rarely told stories. Though so many photographers have made millions of photos in this region, 95% of what they share are colorful testaments to the beauty of their subjects. I want those colors to fill my eyes and frames as well, but I also want my images to impart a sense of local history. I make sets of specific photographs in black and white, the tone them just slightly warm to feel like an earlier time.

From up on Steptoe Butte, a long lens and patient eye is required to isolate ideal compositions from an endless quilt of interlocking patterns. By walking for miles with camera and tripod over my shoulder, I’ve discovered ideal positions and timing for scenes like this. There is superb beauty to anyone who decisively positions themselves to see it. It is an adventure in light.

Despite the multi-hued paint that covers this old sun-scorched Dodge, I chose toned B&W to better reflect the silence of an engine’s final stall.

The region’s citizens are of several faiths, and all I met there are members of a congregation. That’s community, pure and simple as it has been for generations. Through times bountiful or harsh, the many churches of the Palouse region have bound people together. I imagine that these structures still house silent echoes of sermons, ceremonies, laughter and tears of the past. I imagine the voices and creaking floors, and the turning of crisp bible pages.

Here I’m down low with the XF 18-55 at f2.8 to juxtapose the grave and church that held her service.

At the top of a hill sits Freeze Church and cemetery. Here, many old graves reveal clues to the history of the town. Young Margaret Bailey passed before nine years of age. One cannot imagine the void left by of her death, not her family’s tears that have watered her grave. Her headstone has faced west for a hundred years, and has been warmed by several thousand sundowns.

In a historic home I visit each year, a framed newspaper and hanging archives reveal events and the intricate culture who’s people founded and hand-built the region. Times were tough.

“It Might Have Been Worse” and “Devastation of Waters” grace this page.

This lovely still life is in the kitchen of the same home. It’s just one of many poignant gifts of tradition and personal history that I get to share with my workshop participants.

Early morning sun rakes the edges of a a verdant landscape, adding a silent brush stroke of light behind a tractor well out of audible range. This scene repeats annually throughout a verdant rolling panorama. The Palouse is now the nations largest producer of lentils, which are shipped for processing or direct consumption. I hear about new crops almost every time I visit. The world is changing and the farmers must adapt.

Cautious by nature, these sheep keep their distance from curious photo-humans, and a potent electric fence guards their safety from predators. Here, I framed with story in mind, the background giving context to the lone grazing sheep who was just a few feet away. By using a wide angle lens, I am always able to include a subject and it’s environment.

I learned that it is best to preset the camera before approaching, as livestock rarely wait for a photographer fiddling with gear or settings.

One of the more poetic features of this otherwise soft-edged landscape are the many broken Cottonwoods that have survived dozens of thunder storms, winds and icy winters. If someone says “Oh, sure, that’s near that lone broken tree up north”, the tree in question could be the one just down the road, or another a few miles beyond the second dusty red 1952 tractor still used to clear snow by a man named Ned. Regardless, it takes a several visits for the lone photographer to learn where to go beyond the postcard vistas.

Once a busy working vehicle, this rusting sentinel now houses a nest of ornery hornets as it watches the sun set over nearby fields. I imagined the many conversations, songs and sports scores that once filled it’s time-hollowed cab. That is my photographic daydream, adding detail to tell the story in my own style, and choosing compositions that leave room for the eye and imagination to wander.

Grain piles are common near the huge steel silos that dot the region. These wheat kernels are at the heart of any Palouse story, so I took time out to make several closeup portraits.

No matter where you travel or how deep you look, there is a story behind the subject that first attracts you. Try to go beyond the obvious, beyond the popular and the postcard. Tell your story through your own photographs composed by your unique way of seeing the world. I’ll help you find new ways to ‘see’ the Palouse.

~

I’ll be back with more from this series after my next Palouse Workshop. From then on, I’ll endeavor to meet more locals in the region and begin to weave their generous gifts into my writings.

These images were made using a Fuji X-T1 and X-T2 cameras fitted with a 10-24, 12, 16, 56 or 50-140mm lenses. Processed with Lightroom CC Classic, the toned B+W conversions were made using NIK Silver Effects Pro.

Addendum: As of April 5, we have a few spaces left our June 2018 Palouse workshop. We’ve scouted the region, met local people for learning and mapped the best locations for days of striking, clean-air photography. If you’d like great guidance to capture your story of the Palouse and learn of our next tour, subscribe to this blog. Once a subscriber, you’ll automatically be informed of everywhere I go and what I shoot and write. You’ll also get my newsletter with a lot of key info and opportunities to grow as an artist.

~ see you shooting something somewhere,

Dave

I'd love to share my knowledge with you.

Just fill in the blanks to subscribe for more travel stories and techniques in Photography, Lightroom and Photoshop.

I occasionally send out "The Viewfinder" e-newsletter, and provide free presets and workshop discounts.

I never over-post, share your info, and you can opt out at any time.

I’m gonna go back and look at my Palouse photos with B&W in mind. Thanks for the inspiration!

Nice work David. One question. How did you discover the electric fence?

I don’t trust any wire fence that uses insulation blocks as an attachment. Plus, someone who’s name I shall not reveal accidentally touched it and jumped a few feet. :-O

Nice job Dave, endless supply of inspiration out there in SE Washington.

Thanks Eric, your images are proof of that.